| HOME | Automatic translations select here your language |

On the shortage of priests

A statistical analysis of the evolution of the clerical and lay populations of the Church since Vatican II

Jack P. Oostveena and Dominic Doyle

Content:

- Introduction

Evolution of religious congregations since 1950

Evolution of the numbers of baptized Catholics

Number of Catholics per priest

South and Central America

Shortage of priests? The problem

Evaluation

Introduction

While the stated main topic of the Amazon Synod is to address the shortage of priests in the Amazon region, it is clear from the Instrumentum Laboris, that unrelated matters are being introduced. These topics such as the proposal to ordain carefully selected viri probati and the introduction of women deacons are, we maintain, motivated from the evident shortage of priests by the modernist liberal ideology certainly present in the Church since Vatican II. Modernism was, prior to Vatican II, firmly and definitively forbidden by Pope St. Pius X in his encyclical Pascendi and implemented via the syllabus Lamentabilli. The underlying motivation for putting these topics on the agenda of the synod is Liberation Theology, which has been one of the modernist destructive false fruits of Vatican II, and that has been clearly instructed against by both their Holinesses St. Pope John Paul II [ref. 1] and Pope Benedict XVI [ref. 2]

This study evaluates the phenomenon of the shortage of priests in the Church generally and the Amazon area specifically. This evaluation is based on official church statistics published in the Annuario Pontificae and other reliable sources. [ref. 3, ref. 4, ref. 5, ref. 6, ref. 7 and ref. 8]

The shortage of priests is certainly not a new or a stand-alone problem that concerns the Amazon exclusively. In the past, the Church has solved this problem by solidarity, sending religious priests with the help of religious brothers and sisters to the areas that could not provide themselves with sufficient priests. These priests came from Europe and North America mostly. While the priests are mainly responsible for administering the sacraments, the religious brothers and sisters take care of the Catholic life in general, such as the daily prayers, education, especially in catechetic as well as healthcare. However, due to the crisis of faith in Western Europe and North America, the number of ordinations of priests as well as the call to consecrated religious brother- and sisterhood has dropped drastically since the Second Vatican Council.

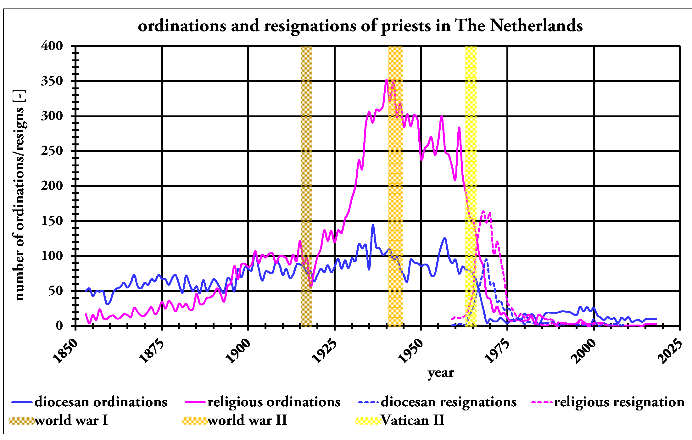

The global source of the shortage of priests, such as manifest in the Amazon, can be illustrated rather pronouncedly in figure 1, which gives an overview of the numbers of priestly ordinations in The Netherlands since the restoration of the Dutch hierarchy in 1853. Due to the fact that before the Council the number of diocesan ordinations were sufficient, almost all religious were at work on the missions.

| Figure 1; Number of ordinations of priests in the Netherlands |

As a result, it is a remarkable fact that from such a small country as the Netherlands, with about 2.5 million faithful in 1925 to 4.5 million in 1960, more than 9,000 religious missionary priests and many more religious brothers and sisters, went to work all over the world during the 35-year period before the Council. However, this stopped dramatically between 1960 and 1970 following by a wave of resignations between 1965 and 1975. A crisis of faith seemed to have spread all over Western Europe and North America. While 1965/1970 can be considered as a clear turning point, this is now about 50 years ago, and therefore even the last members of this group of priests are now dying out. Although less pronounced, the same tendency can be observed in the worldwide statistical overview of the evolution of the numbers of religious priests and brothers.

This additionally means that the serious shortage of priests becomes more and more apparent.

Evolution of religious congregations since 1950

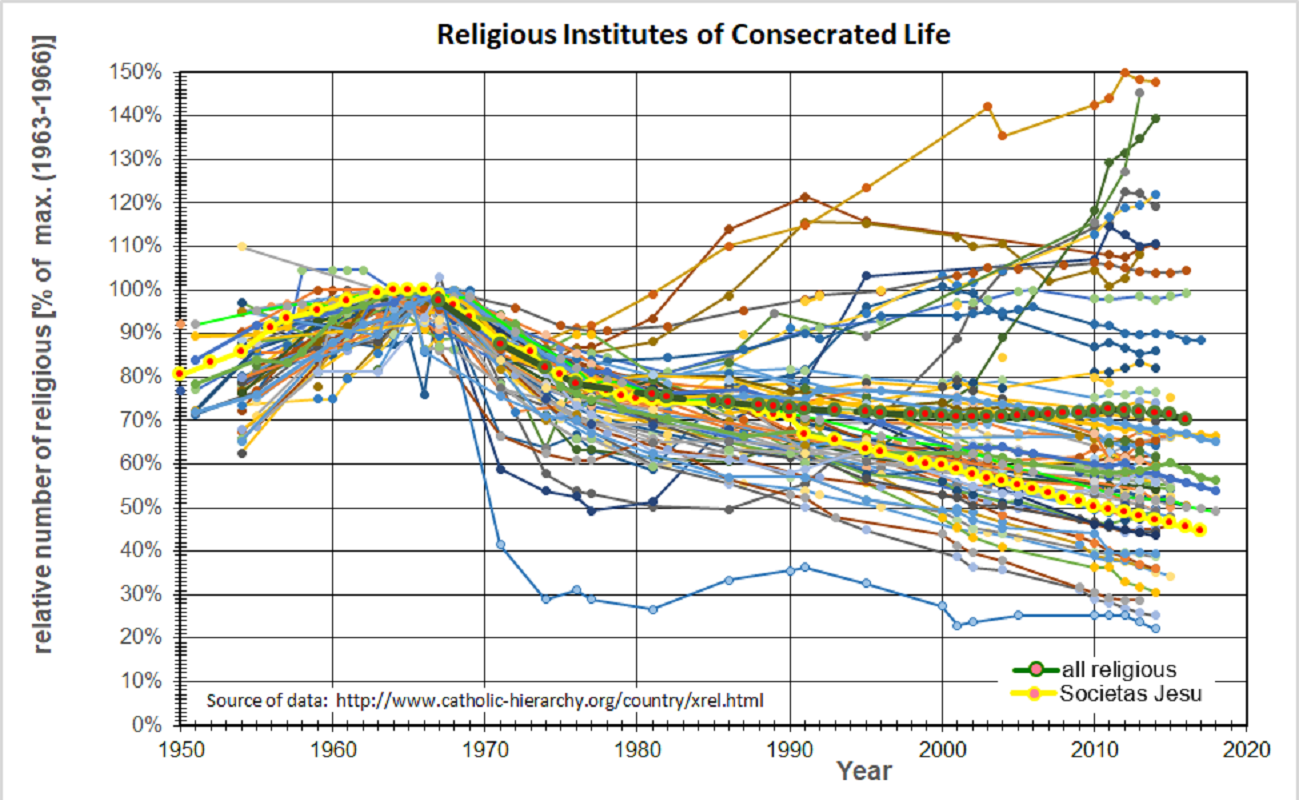

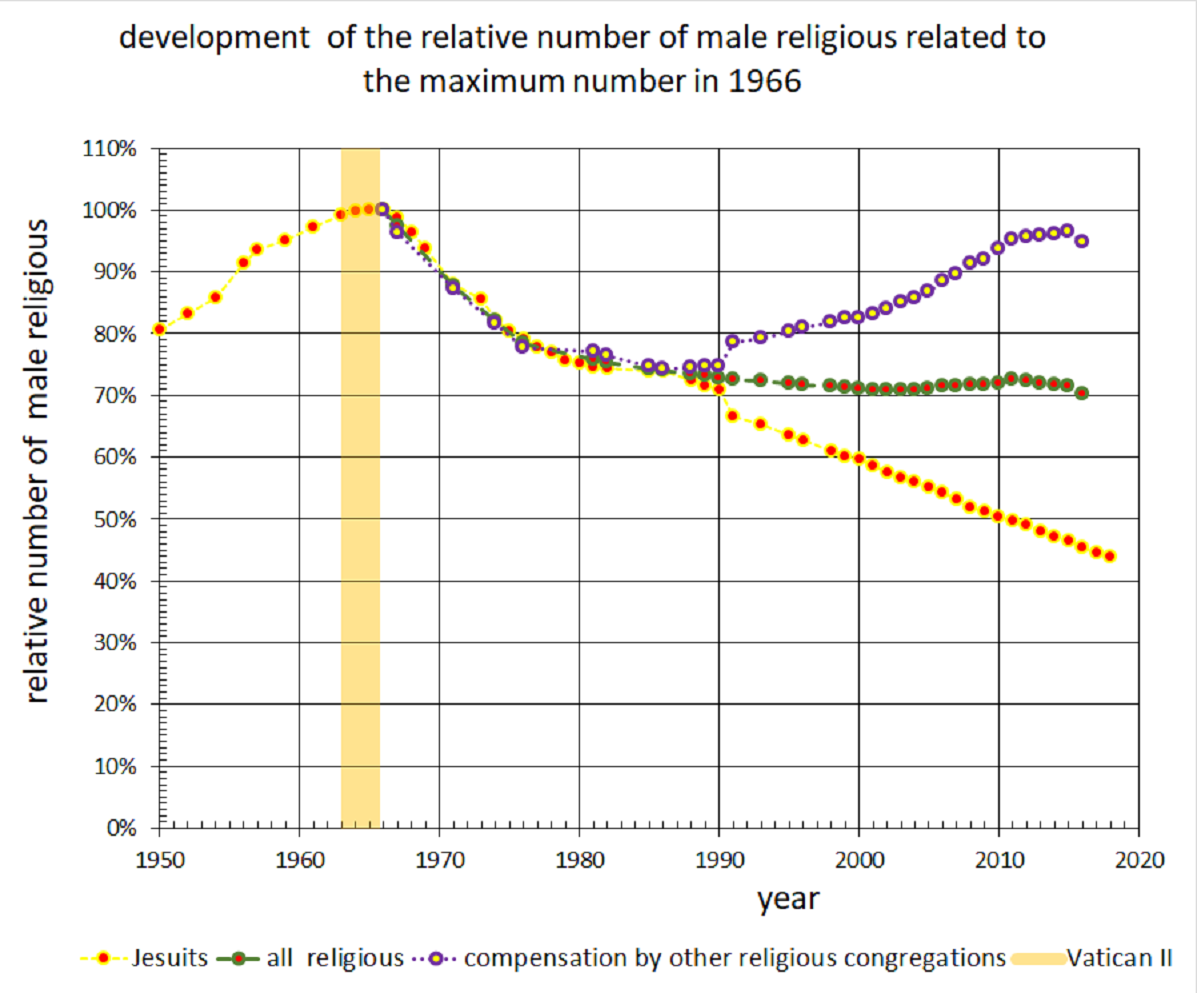

The statistics show clearly that for most if not almost all of these congregations, a relative maximum number of male religious (priests and brothers) occurred between 1964 and 1967 (Figure 2). This maximum is arbitrarily set at 100% for convenience in these analyses. Thereafter, during the first decade following the Council a relative drop of between 10% and 40% occurred, and for some congregations this was even greater. The comparative relative drop of the total numbers of religious members (highlighted dark-green/red in figure 2, figure 4 and figure 5) within these individual congregations during this decade was about 20%.

| Figure 2; Relative number of religious related to the maximum number of religious during the period 1964-1967 |

Then, after this downfall, the total number of all religious members stabilized during the next 20 years at a level of about 70% of the maximum. On the one hand that means a primary loss of about 99,000 male religious members until 1995 and on the other hand it also means that since 1995 as an overall average each religious during his religious lifetime is inspiring only one new religious vocation: no loss, but also no growth.

Although, globally, the number of male religious, priests and brothers, is rather constant since 1995, this is merely a balance between male religious congregations that are still in severe decline and those that now are in a renewed or partly renewed growth. Figure 2 shows the large scatter for the individual congregations over time, between those with a renewed or partly renewed growth after the first decade post Council, and those remaining under severe decline up to the present. If the lack of vocations in these congregations continues, they will ultimately die out completely.

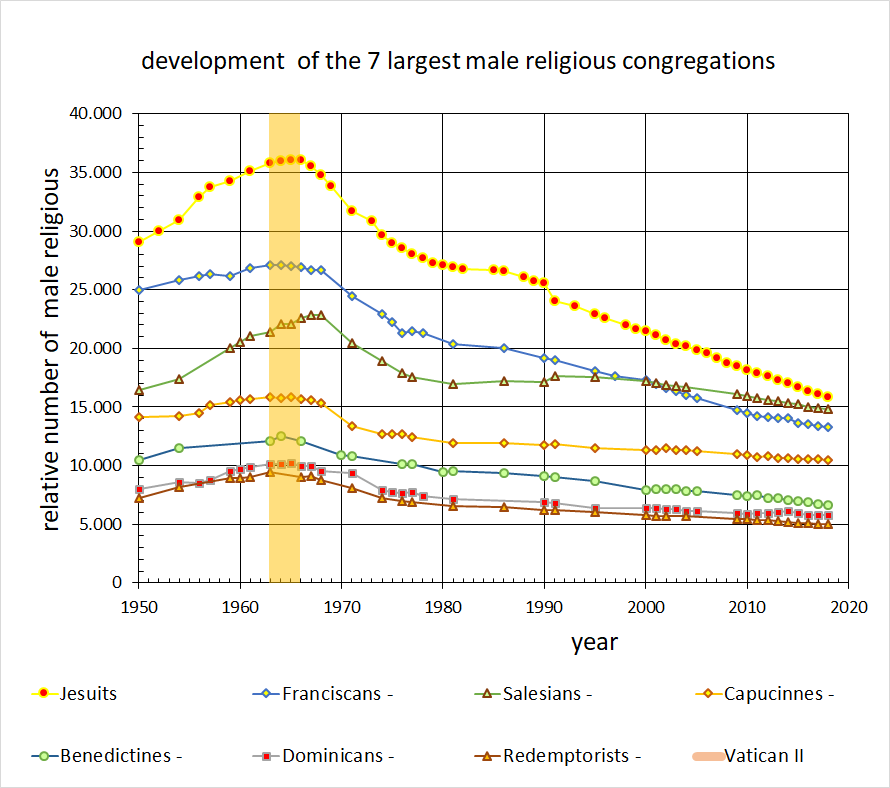

| Figure 3; The evolution of the numbers of religious concerning the seven largest religious congregations |  |

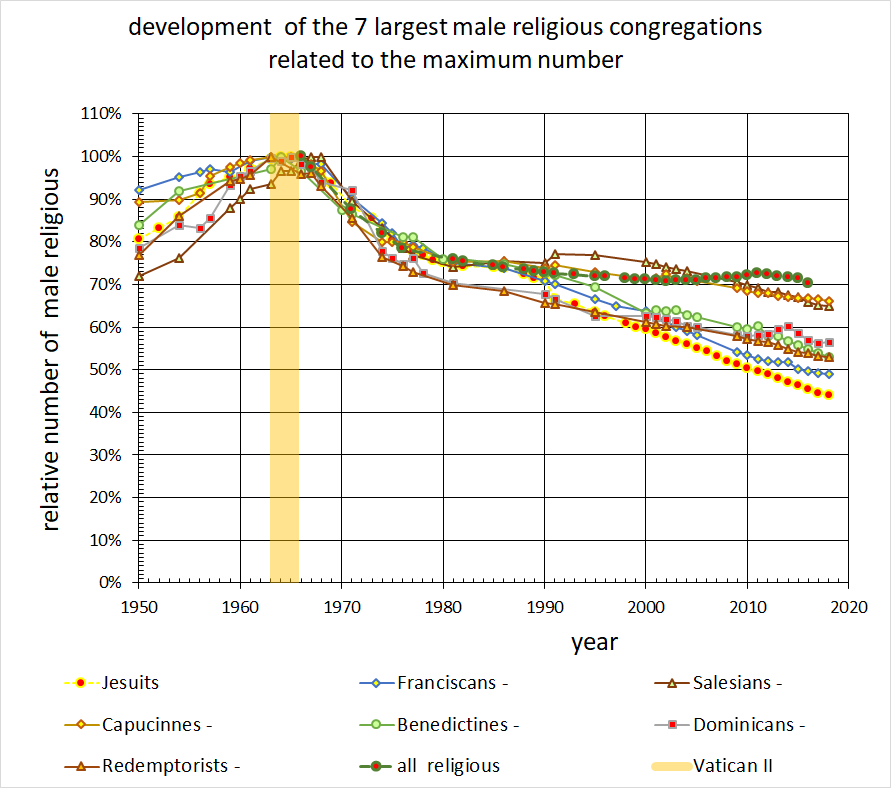

| Figure 4; Relative numbers of religious concerning the seven largest religious congregations |

It is clear that none of the seven largest congregations have experienced a renewed growth. Besides the Capuchins and the Salesians, whose numbers have remained relatively stable after first decade, they all suffered serious declines (figure 3 and figure 4). The seven largest congregations have contributed to the primary loss of the religious members with a loss of about 18,850 priests and 24,000 brothers before 1995, which is about 43% of the total primary loss. Then, because these congregations are still in severe decline, they are also accountable for a further loss of about 12,550 priests and 6,700 brothers after 1995. About 61% of this decline is directly attributable to the Jesuits (S.J.) and Franciscans (O.F.M.).

Highlighting the Jesuits in particular (marked yellow/red in figure 2 through figure 5 ), show a relative decline compared to the totals until about 1990. Since 1990 the Jesuits continue to decline at a steeper rate of about 10% per decade, up to the present day without any sign of change. Since 1966, the Jesuit population of about 36,000 has declined to 15,800 in 2018, which is a reduction of about 56%. If this rate of decline continues, the Jesuits will be reduced to a very small unimportant society with less than 1000 members within a period of 50 years from now.

| Figure 5; The compensation of the religious congregations in severe decline by other religious congregations |

Taking again the example of the Jesuits, the fact that since 1995 the total number of all-religious is rather constant means that these congregations in severe decline are compensated by other congregations that are growing (figure 5). This compensation shows that renewed growth as seen already prior to the Council is still possible. However, objectively, the fact that, despite this renewed growth, the total number of all religious members remains rather constant since 1995, is still a negative sign and is showing in fact a secondary loss of religious. The example of the Jesuits shows here that instead of a decline to 44% (today) of the number of Jesuits in 1966, this society could have grown at about 10% per decade to around 150%. Thus instead of the actual 16,000 Jesuits the number of Jesuits could have potentially been 54,000, which indicates a total evaluated loss, primary and secondary, of about 38,000 Jesuits.

Evolution of the numbers of baptized Catholics

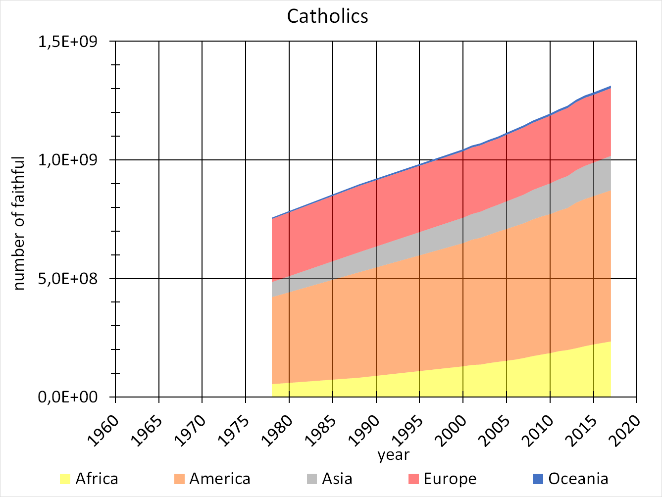

According to statistics provided by Agenzia Fides [ref. 5], the number of baptized faithful globally grew from 7,500 million in 1978 to 13,000 million in 2017, which corresponds to a growth rate of 1,9% per year (figure 6). This justifies the use of a conservative estimate of an expected growth of the total religious members of at least 1% per year, in order to determine the secondary loss of religious due to the actual lack of growth since the Council. This results in a secondary loss of about 165,000 religious members that, when coupled with the primary loss of 99,000 religious members gives a potential loss of about 265,000 members. Thus, instead of the actual 231,000 number of religious, the total could have been at least about 495,000, of which at least 50% would be religious priests. This affects the entire Church and thereby all humanity. This significant loss of religious who, for centuries worked worldwide at locations with insufficient local vocations has especially handicapped the Church and her mission.

| Figure 6; The evolution of the world wide number of baptized faithful per continent since 1978 |

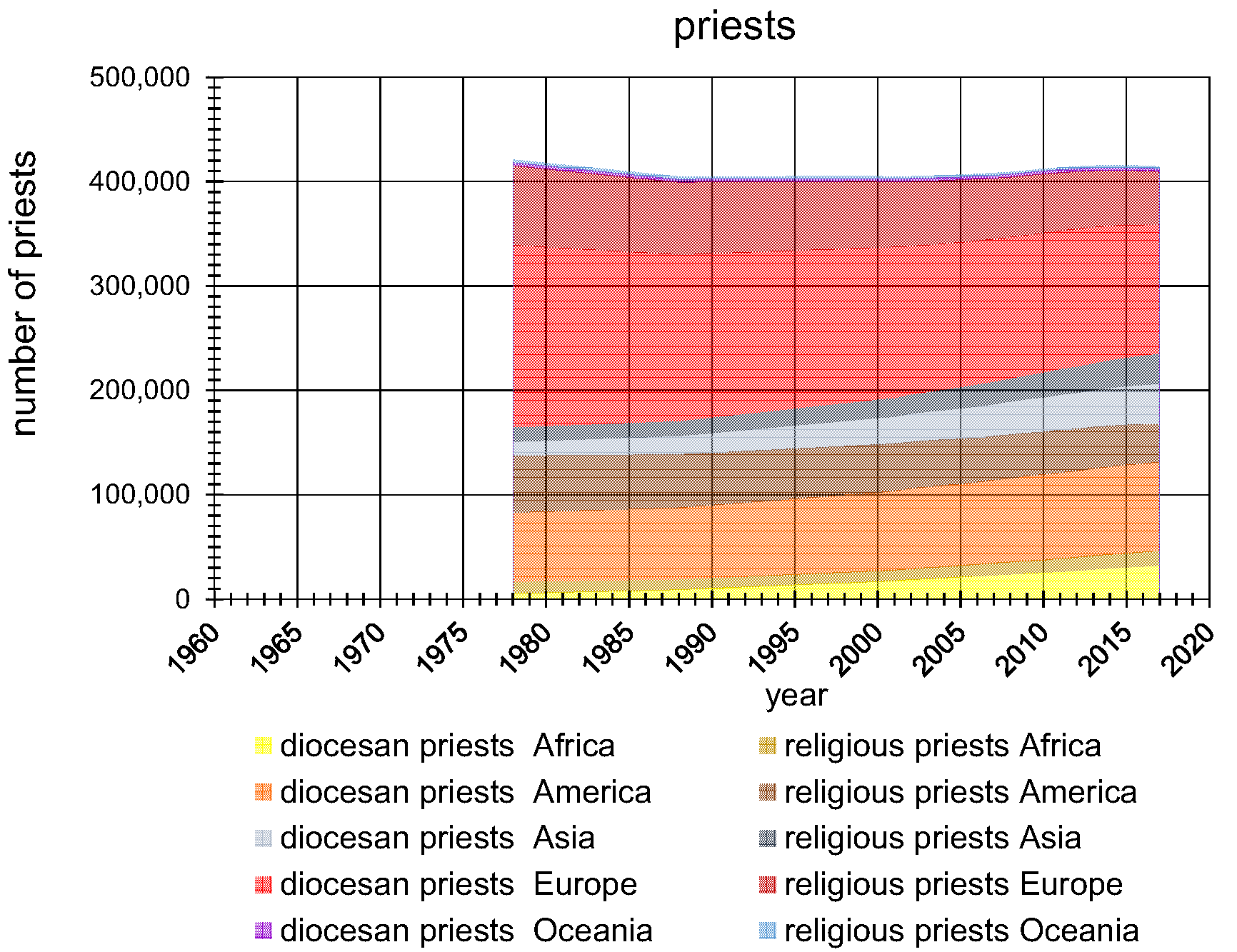

| Figure 7; The evolution of the world wide number of diocesan and religious priests per continent since 1978 |  |

Additionally, the evolution of the religious members illustrated in figure 2 is a selected set of individual congregations, which taken together represent about 86% of all religious in 1966. In 2014, these same congregations represented about 74% of all religious members only. Obviously, the congregations not included in these statistics represented 14% of all religious in 1966 and has increased proportionately to 26% in 2014. With regard to the relative baseline of 100% in 1966 this means that these congregations that are outside the known statistics have undergone an average growth of up to 130%.

Number of Catholics per priest

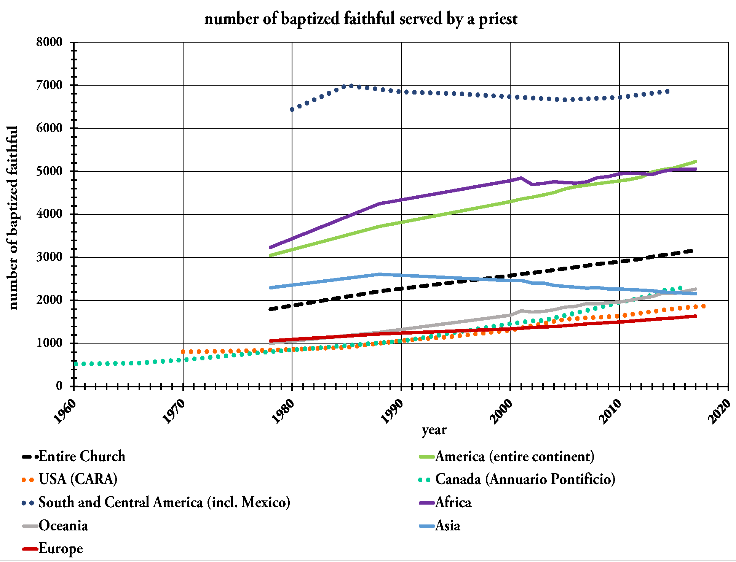

The number of faithful per priest is often used to prove the shortage of priests, especially if the numbers of faithful is increasing. This measure is relative and shows only the proportionality between the numbers of faithful and the numbers of priests.

The continuing growth in the number of baptized Catholic faithful (figure 6) and the lack of a corresponding growth in the priesthood (

The Asian continent shows a peak of about 2,600 faithful per priest in 1988 where after this number has been slowly but steadily decreasing [ref. 6]. All other continents demonstrate a growing trend in the numbers of faithful per priest and with that a lack of vocations to serve them. It is interesting to observe and note that these statistics provide clear evidence that the average situation in Africa is more or less comparable with average for the entire continent of America.

| Figure 8; The evolution of the number of baptized faithful per priest per continent, inclusive North America (USA and Canada) and South and Central America (including Mexico) |

The continent of Europe with a rather constant number of faithful and a decreasing number of priests, results in an average growth of the number of faithful per priest. In contrast, the entire American continent (North and South) shows a growth of the number of faithful but with a rather constant number of priests, which also results in a growing average number of faithful per priest. Of course, the average numbers of faithful per priest is a kind of balance between local dioceses that therefore can differ a lot within each continent. So, with regard to the continent of America, the evolution of the proportionality has to be considered to be a balance between North and South. This balance can be seen in figure 8 which shows that the evolution of the number of faithful per priest in North America increases from about 900 in 1970 to 2,000 in 2017 for the USA [ref 7] and from 500 in 1960 to 2,300 in 2016 for Canada [ref. 3] respectively. Taking into account these specific data concerning America, the evolution of the number of Catholics per priest for South and Central America including Mexico can also be determined. This average value is rather constant between 6500 to 7000 faithful per priest during the entire period observed, 1980 - 2016.

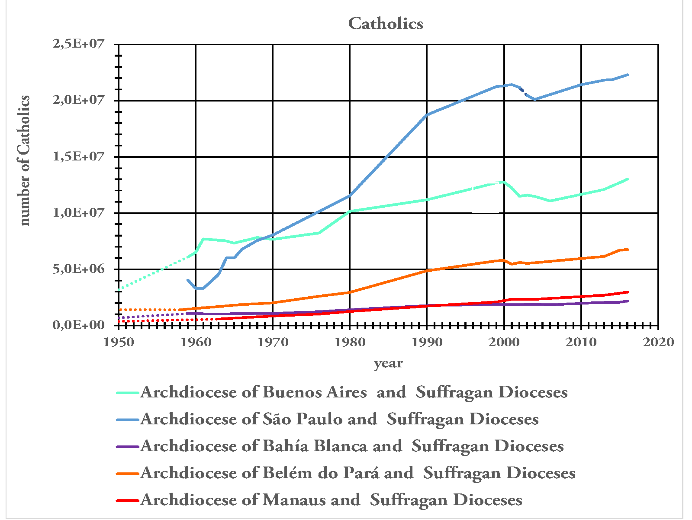

| Figure 9; The evolution of the number of Catholics of the five South American areas.- five Archdioceses with 50 suffragan dioceses |

South and Central America

It is most striking and quite remarkable to observe that the average situation for South and Central America is rather constant at a level of one priest per 7,000 baptized faithful since 1985. Despite this lack of change over several decades, the local situations in South and Central America can indeed differ a lot as shown by some samples taken from South America at diocesan level.

Using data provided in the Annuario Pontificio [ref. 3 and ref. 4] statistics have been extracted for a sample of two Argentinian and three Brazilian regions. The results are presented in figure 9 to figure 12. On the one hand, we find here a first region, the Archdioceses Buenos Aires (Argentina) and its twelve suffragan dioceses that comprise a total of about 13,000,000 Catholics, and a second region of Archdioces Sao Paulo (Brazil) with its ten suffragan dioceses having about 27,000,000 Catholics. Both regions are strongly urbanized with about 2,200 Catholics per square kilometer. On the other hand the third region provided by the Archdiocese of Bahia Blanca (Argentinia) and its seven suffragan dioceses that has about 2,200,000 Catholics, the Archdiocese of Belém do Pará (Brazil) and its thirteen suffragan dioceses as the fourth region has about 6,800,000 Catholics and the fifth region, the Archdiocese of Manaus (Brazil) and its eight suffragan Dioceses, comprise 3,000,000 Catholics. These last three regions are thinly populated with 2 to 4 Catholics per square kilometer. The last two regions specifically concern the Amazonian area. The Archdiocese of Belém do Pará and its suffragan dioceses (1,435,127 km2) concerns the whole Brazilian province of Pará including the Amazon delta, while the Archdiocese of Manaus and its suffragan Dioceses concern an inland part of the Brazilian Amazon area (1,348,025 km2).

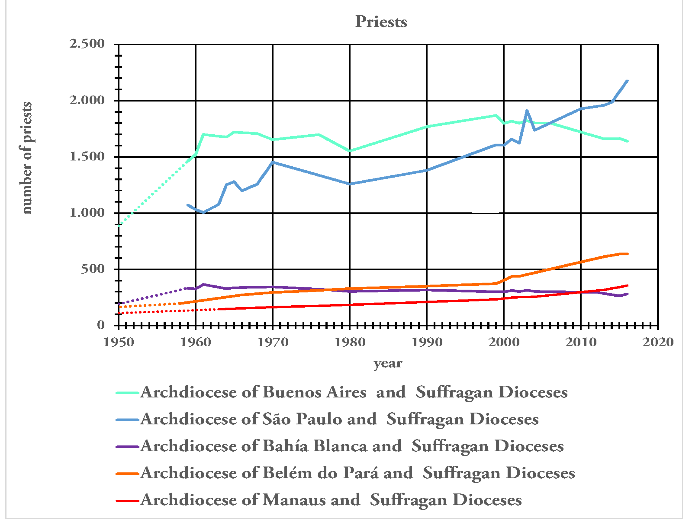

| Figure 10; The evolution of the number of priests of the five South American areas - five Archdioceses with 50 suffragan dioceses |

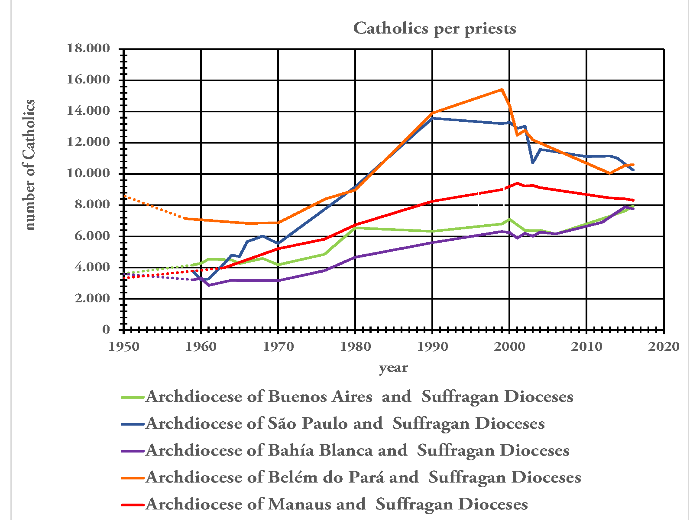

| Figure 11; The evolution of the number of Catholics per priest of the five South American areas.- five Archdioceses with 50 suffragan dioceses |  |

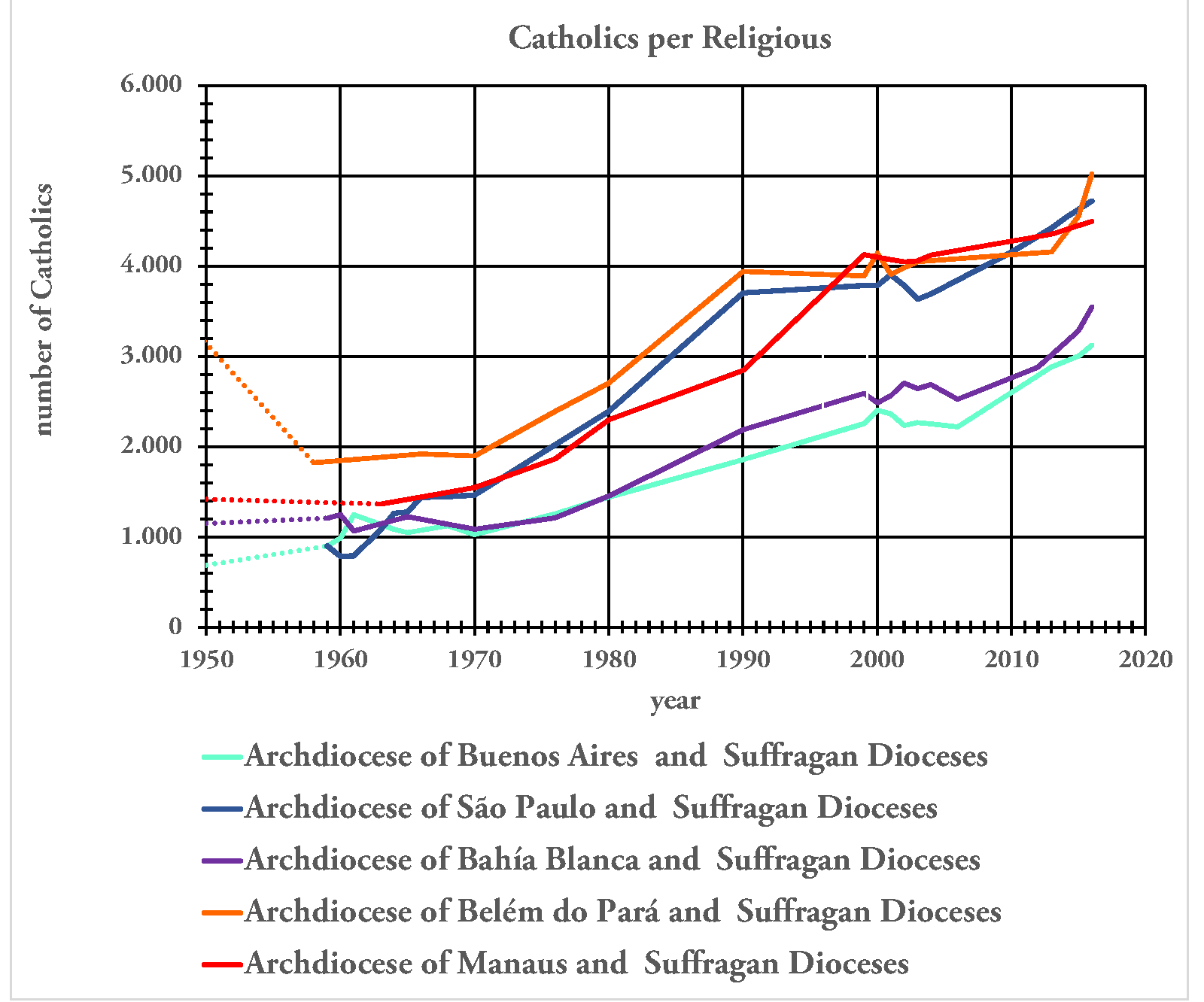

| Figure 12; The evolution of the number of Catholics per religious of the five South American areas.- five Archdioceses with 50 suffragan dioceses |

While figure 9 gives an impression of the growth in numbers of Catholics over time since about 1950, Figure 10 shows the number of priests as a balance between the decreasing number of religious and increasing numbers of diocesan priests. The number of Catholics per priest is a relative measure that depends on both, the number of Catholics (figure 9) and the number of priests available (Figure 10). That means that a change of the numbers of both, the Catholics and the priests will influence independently the balance in the number of faithful per priest. The evolution of this balance since about 1950, including the average for South and Central America (including Mexico) is given in figure 11. Additionally the evolution of the number of Catholics per lay-religious, both religious brothers and sisters, can be found in figure 12.

Very interestingly, these statistics do not show a characteristic difference between the urban and non-urban areas. In contrast to such suggestions, for both Argentinian regions, Buenos Aires and Bahia Blanca, the growth in numbers of Catholics per priest as well as per lay religious are similar. While until about 2010 the average number of Catholics per priest for both Argentinian regions were still below or equal to the average of about 7,000 for the entire South and Central America this value increased to about 8,000 faithful per priest in 2016. In contrast with the situation in the Argentinian regions, the Brazilian regions show a different evolution. While this balance for the region Manaus grew from about 3,000 to 9,000 Catholics per priest in 2001, the other two Brazilian regions, Sao Paulo and Bélem do Pará, show a different trend. They increased from about 4,000 faithful per priest in 1960 up to 13,000 during the period 1990 and 2000 and from 9,000 in 1950, through a decline to about 7,000 during the period 1970 and 1980 to about 15,000 in 2000 respectively. Since 2000, the number of Catholics per priest has been decreasing continuously for those Brazilian regions, due to an increase in the number of diocesan priests. The region of Manaus decreased from 9,000 to about 8,000 Catholics per priest in 2016 while the other two regions decreased from about 13,000 and 15,000 in 2000 respectively to about 10,000 in 2016.

It is important to comment on the the balance of the numbers of faithful per priest with regard to the averages of the regions analysed i.e. five Archdioceses and their 50 suffragan dioceses. Although the level of Catholics per priest for these regions observed is still high, it is very important to note that no significant difference between the thinly populated areas of the Amazon and the urban areas can be observed. Of particular note is that the Brazilian areas evaluated here, have found a way to increase of the numbers of diocesan priests in order to reduce the numbers of faithful per priest.

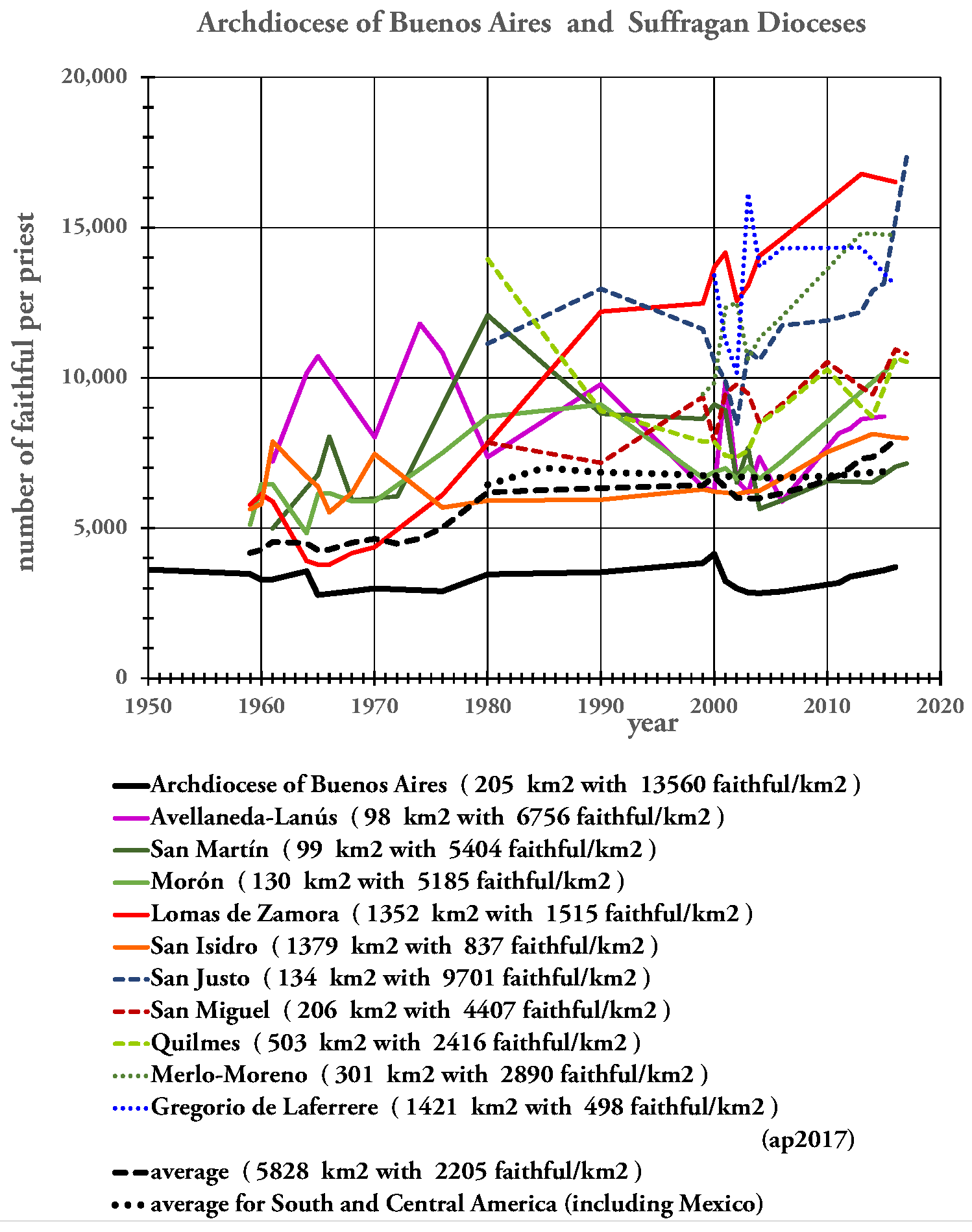

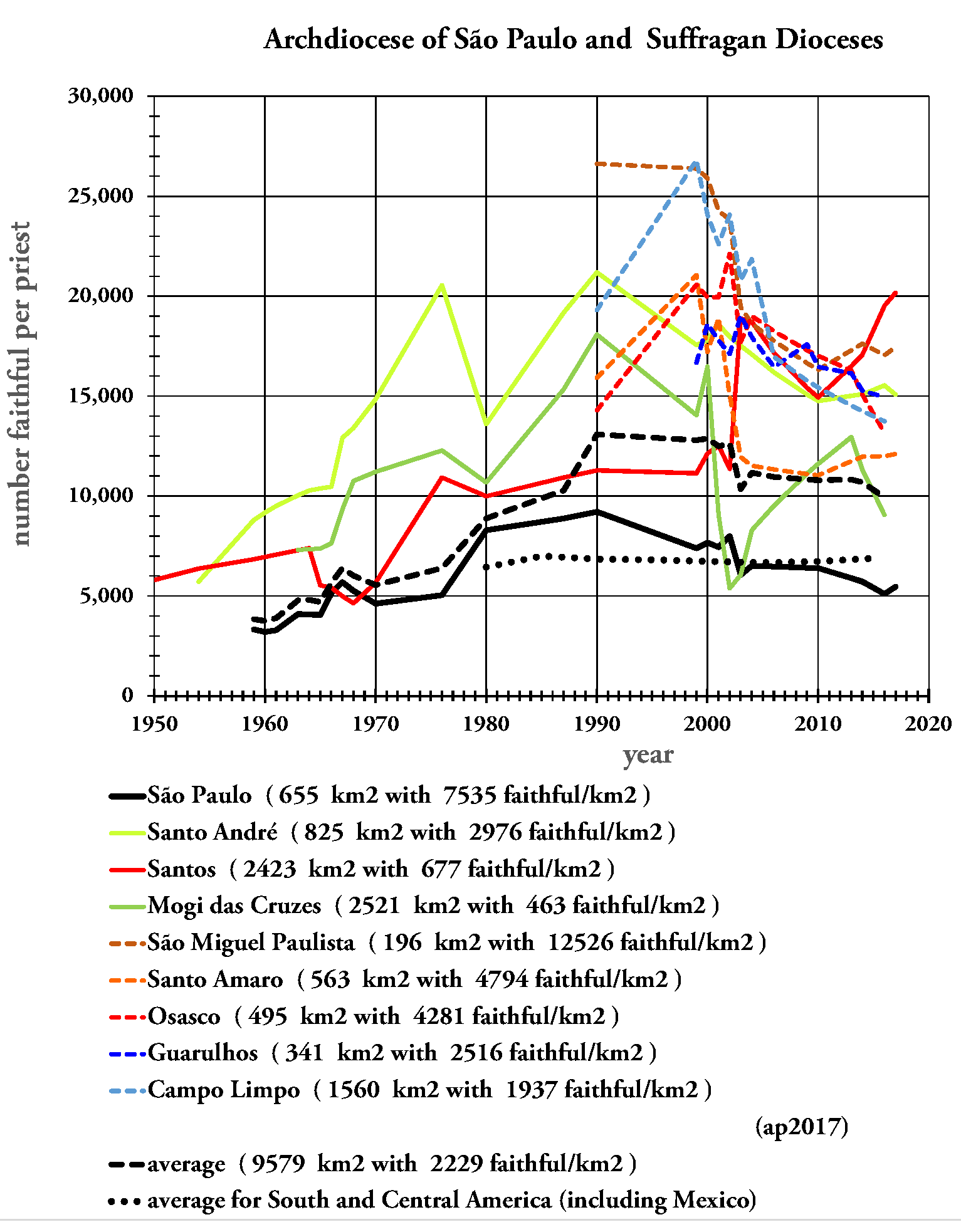

Furthermore, because of the rather constant level of about 7,000 faithful per priest in South and Central America it has to be concluded that in contrast with these results for the five regions analysed and discussed above, other regions in South and Central America must have on average a better situation. In fact this can also be observed within the considered regions. As an example: in the region of Buenos Aires with an actual average (2016) of about 8,000 faithful per priest, the number of faithful per priest in the Archdiocese varies during the observed period since 1950 till today between 3,000 to 4,000 faithful per priest. However note that its suffragan dioceses actually have to suffer under the pressure of 7,000 to even 17,000 faithful per priest (figure 13). The same trend can observe at the region of Sao Paulo (figure 14).

| Figure 13; Internal distribution of the regio Buenos Aires over the Archdiocese and its suffragan dioceses |

| Figure 14; Internal distribution of the regio Sao Paulo over the Archdiocese and its suffragan dioceses |  |

Certainly, as seen from the situation of Buenos Aires the extremely high numbers of faithful per priest are not by definition the thinly populated locations. Another example can be observed in table 1 concerning the Archdiocese of Lima (Peru). In December 1996 three new suffragan dioceses namely: Carabayllo, Chosica and Lurín were established after being separated from the Lima Archdiocese. Table 1, taken from the Annuario Pontificium 2000 and 2017 [ref. 3 and ref. 4], shows a total contrast between what happened in Lima and how the situation evolved in the three suffragan dioceses between 1999 and 2016 respectively. In contrast to the3,941 faithful per priest in the Lima Archdiocese, the number of faithful per priest, in the three suffragan dioceses, varies between 14,000 and 34,000 for the year 1999. The average number of faithful per priest for this entire area (Archdiocese and the three suffragan dioceses) is then 8,270 faithful per priest. Although the numbers of faithful per priest in the suffragan dioceses has improved from 29,765 in 1999 to 20,343 in 2016 (for Carabyllo), from 14,028 to 11,440 (for Chosica) and from 34,615 to 12,106 (for Lurín) respectively, these numbers are still in great contrast with the situation in the Archdiocese of Lima, which has remained essentially constant over the same period. Moreover, none of these dioceses can be compared with the thinly populated areas of the Amazon with 2 to 4 faithful per square kilometre.

Archdiocese of Lima with the three suffragan Dioceses established December 1996 | ||||||

| Year | (Arch-)Diocese | Number of Catholics | Number of priests | Number of faithful per priest | Surface in km2 | Number of faithful per km2 |

| 1999 (ap2000) | Lima | 2,880,720 | 731 | 3,941 | 639 | 4,508 |

| Carabayllo | 1,785,905 | 60 | 29,765 | 1,504 | 1,187 | |

| Chosica | 1,234,497 | 88 | 14,028 | 3,418 | 361 | |

| Lur�n | 1,800,000 | 52 | 34,615 | 808 | 2,228 | |

| Total / average | 7,701,122 | 931 | 8,272 | 6,369 | 1,209 | |

| 2016 (ap2017) | Lima | 2,412,153 | 612 | 3,941 | 639 | 3,775 |

| Carabayllo | 2,522,473 | 124 | 20,343 | 1,504 | 1,677 | |

| Chosica | 1,716,000 | 150 | 11,440 | 3,418 | 502 | |

| Lur�n | 1,210,624 | 100 | 12,106 | 8089 | 1,498 | |

| Total / average | 7,861,250 | 986 | 7,973 | 6,369 | 1,234 | |

In this specific case of the Lima Archdiocese and these three of its suffragan dioceses, one can rightly wonder where the responsibility lies for that great contrast between the Archdiocese and its suffragan dioceses. In other words, how can one establish dioceses with such a low number of priests per faithful? Who was responsible for creating these suffragan dioceses under these specific circumstances? Anyway, this example shows a total lack of solidarity even among neighbouring family-dioceses.

Shortage of priests?

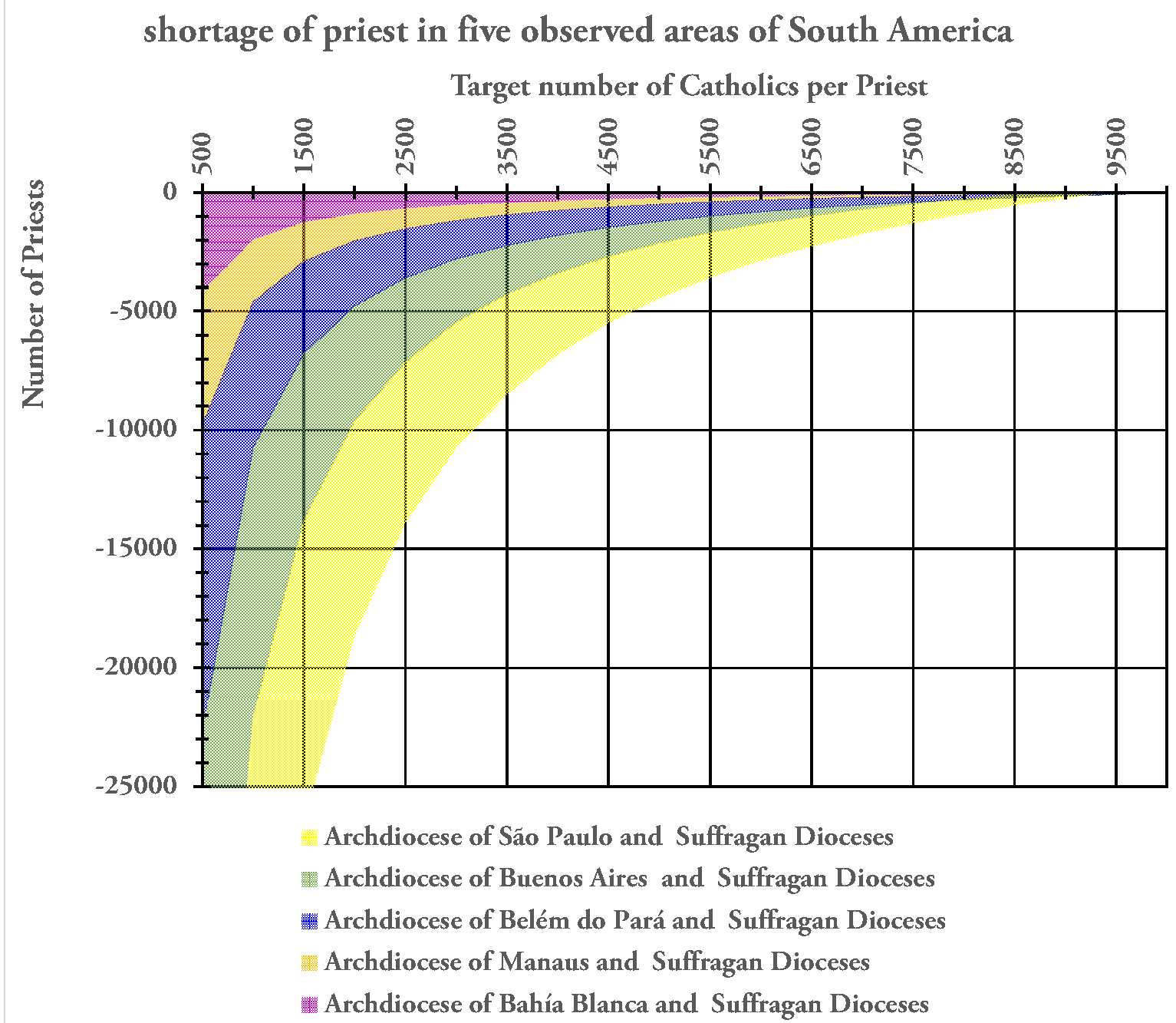

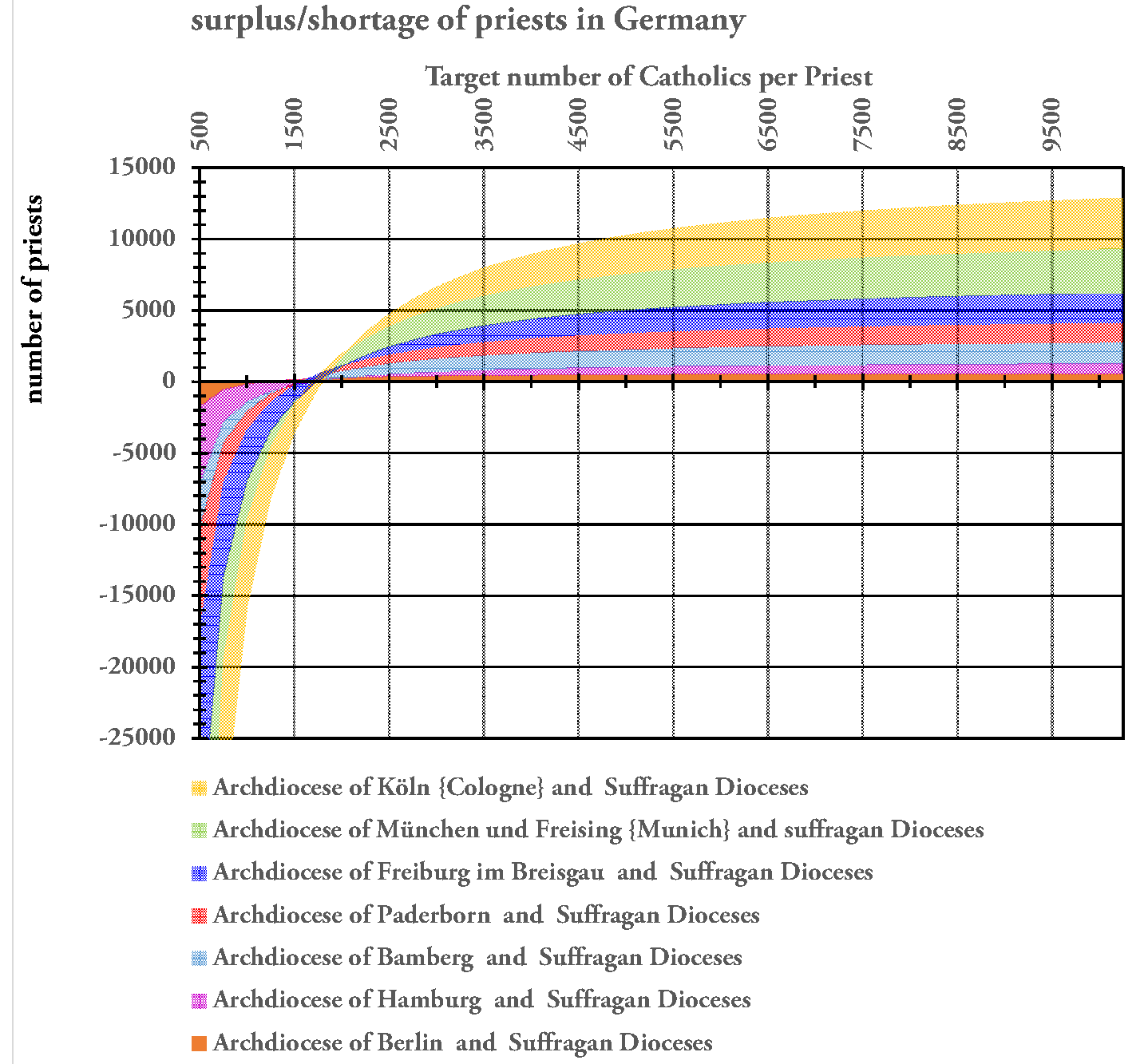

Considering the question of the shortage of priests, this must be analysed and evaluated carefully with respect to what the preferable target for the number of Catholics per priest should be. Based on the statistical data from the Annuario Pontificum 2017 [ref. 5] an analysis of the relationship between a target number of Catholics per priest and the shortage of priests is presented in figure 15 for the five South America locations previously analysed above. In order to provide a meaningful comparison, a similar analysis is also presented for Germany (figure 16).

| Figure 15; The shortage of priests as function of the number of Catholics per priest in the five South American areas |

| Figure 16; The shortage/surplus of priests as function of the number of Catholics per priest in the Germany |  |

So what should the preferable target value of numbers of faithful per priest be? Should it be different per continent? How can we establish this number in a reasonable way?

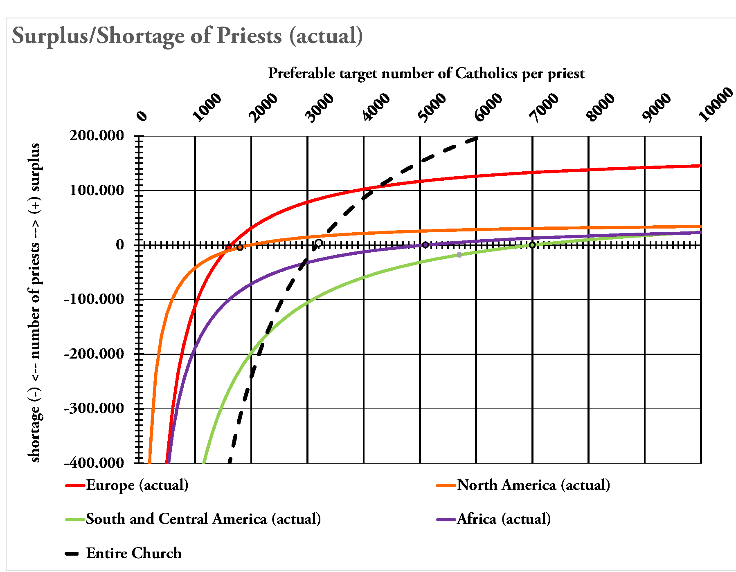

Is it a random number of Catholics per priest, is it the historical number prior to the Council, or should it be the actual average number for the entire Church, namely about 3,100 Catholics per priest (Figure 8)?

| Figure 17; The actual shortage/surplus of priests as function of the number of Catholics per priest for the entire Church, Europe, North America, Africa and South and Central America |

This last option (actual global average of number of faithful per priest) means that the entire Church suffers in solidarity with those countries suffering now from a large shortage of priests; namely the continents of Africa, South and Central America. With regard to this average of about 3,100 Catholics per priests, figure 15 roughly shows that the actual shortage of priests for the five observed areas in South America is about 10,000 priests. However taking into account the entire continent of South and Central America as well as Africa this shortage is about 130,000 priests nominally (figure 17). Thereby, the local differences between the several countries as well as among dioceses that very often cannot be redistributed are not taken into account, which make the real shortage even greater.

The problem

When religious congregations cannot fully fulfil their mission, it should be the duty of solidarity that obliges the Church, even at the diocesan level, to help the parts that are suffering. Although the shortage of religious priests has been observed and foreseen for many years, nobody seems to have taken the responsibility and necessary measures to address the consequences.

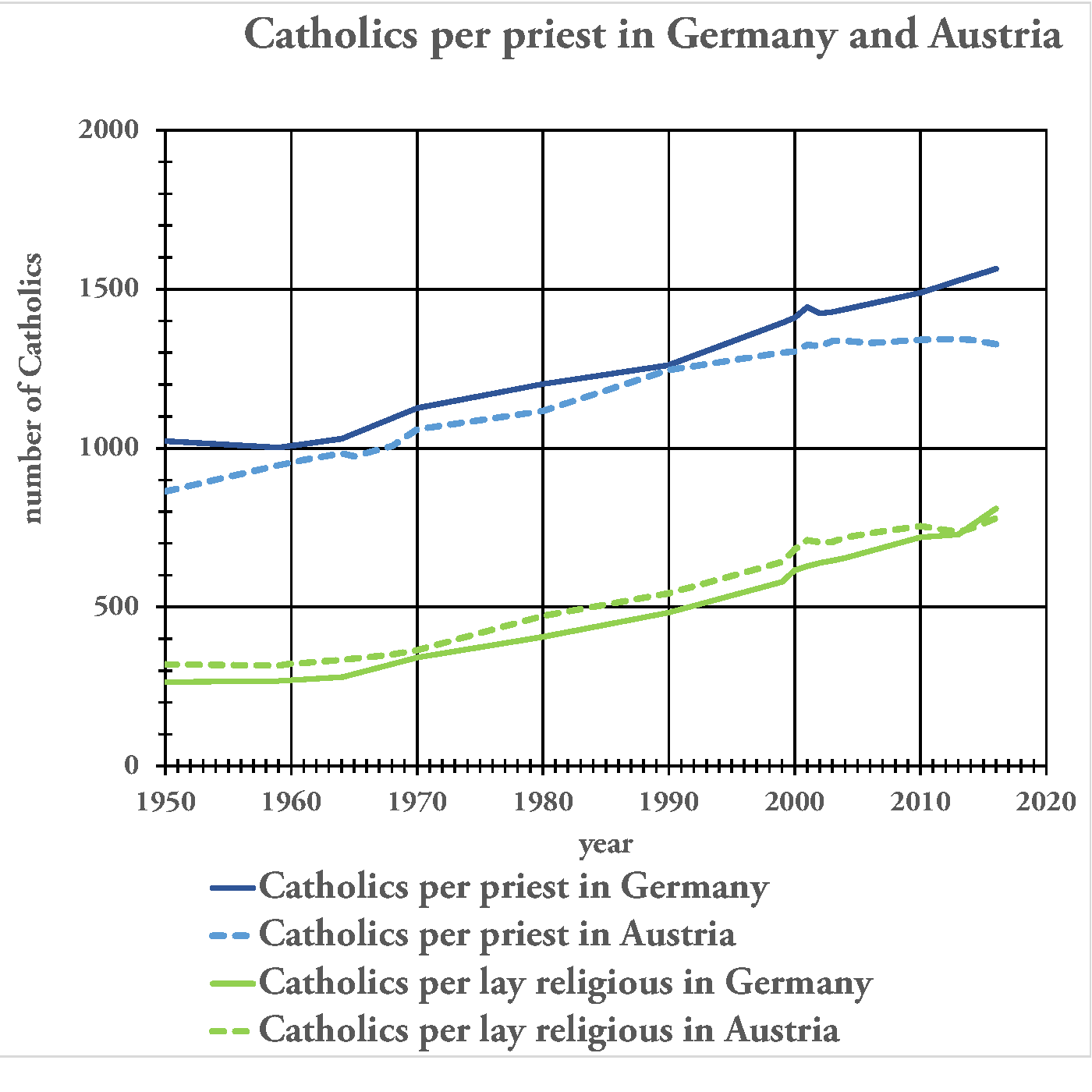

Therefore, those countries that claim a shortage of priests because they moved from a situation of about 500 to 1,000 faithful per priest prior to the Council to about 1,500 to 2,000 faithful per priest today also bear a heavy responsibility towards all these suffering areas. For example Germany with an actual average of about 1,600 Catholic faithful per priest (figure 18) could have made preparations for sending about 7,500 priests to help these suffering areas, while keeping themselves at a level of about 3,000 faithful per priest. Either, one can continue propagating the ongoing catastrophe or one can start the process of recovery by returning to both the original missionary and contemplative spirit of the Church.

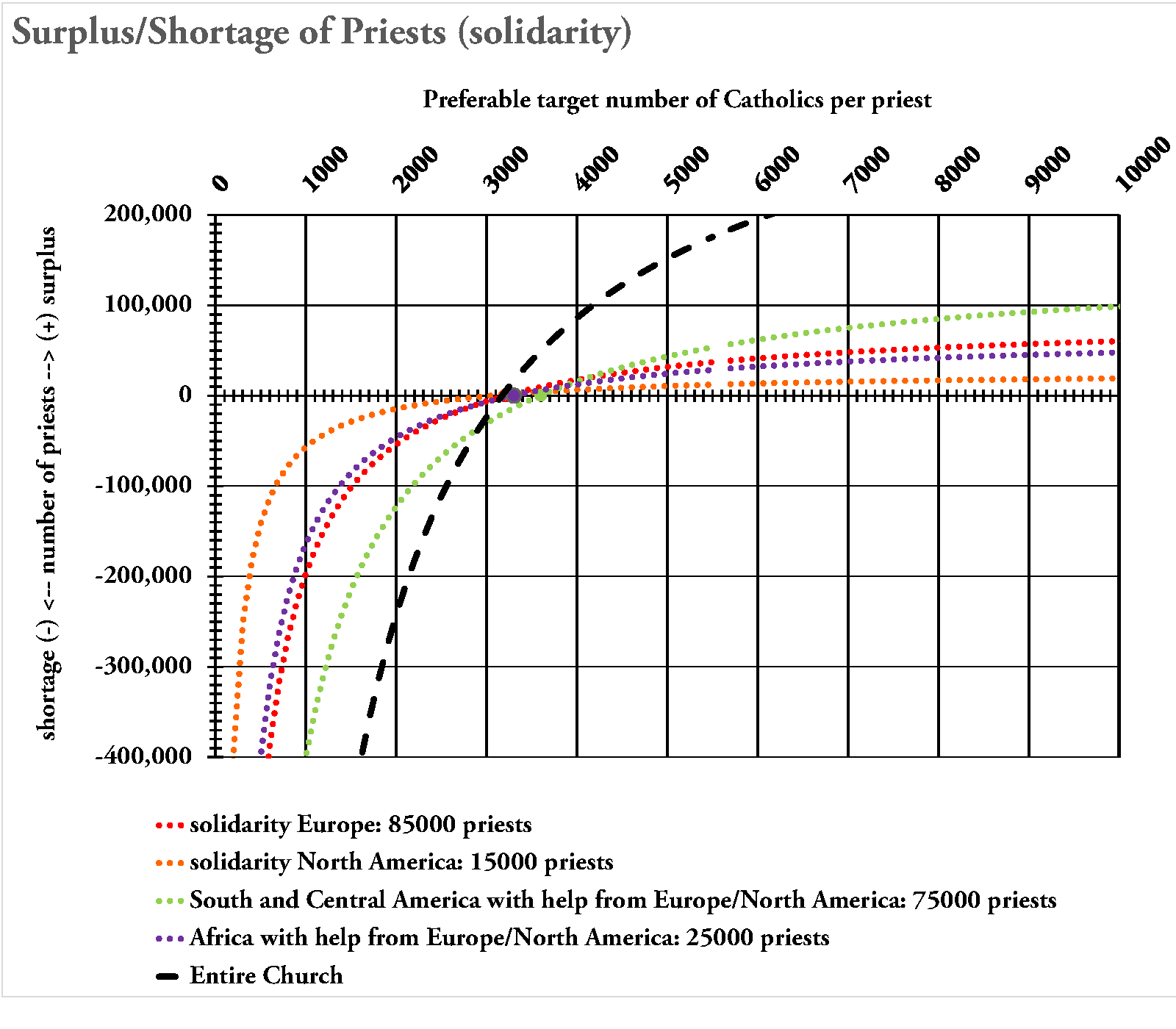

Based on the actual average number of about 3,100 baptized faithful per priest for the entire Church (figure 9), Europe and North America can be stated to have a surplus of about 85,000 and 15,000 priests respectively. In such a way South and Central America could be provided with about 75,000 priests, while Africa with 25,000 priests by which an average balance of these continents become between 3,200 and 3,500 faithful per priest (figure 17 and figure 19). In order to maintain solidarity within the global Church, North America and Europe could have prepared to promote temporary missions among their diocesan priests to help these truly suffering areas in South America and Africa to survive and work towards a better future.

Such actions of solidarity would demonstrate a more responsible attitude, than misusing this Amazonian shortage to claim that the ordination of carefully selected viri probati would be the true solution. The solidarity approach would have huge consequences as can be seen in table 2. This table expresses the shortage of priests for a range of target values for the numbers of faithful per priest: 2000, 3000, 4000 and 5000 in absolute numbers as well as in percentages referring to the local priesthoods in 2016. Evidently, the solution for the shortage of priests by recruiting carefully selected viri probati in these South American areas does not work! Apart from the fundamental theological objections to the ordination of married men, the consequences for the priesthood would be enormous, if it would indeed be possible to find so many carefully selected viri probati to solve this shortage (table 2). The celibate priesthood would then be completely overwhelmed by these euphemistically called viri probati

Shortage of priests | |||||||||

| Number of priests in 2016 (ap2017) | Preferred target number of faithful per priest | ||||||||

| 2000 | 3000 | 4000 | 5000 | ||||||

| [-] | [%] | [-] | [%] | [-] | [%] | [-] | [%] | Archdiocese of Buenos Aires and its suffragan dioceses | 1,640 | (4,848) | 296 | (2,677) | 163 | (1,592) | 97 | (941) | 57 |

| Archdiocese of Bah�a Blanca and its suffragan Dioceses | 1,640 | (4,848) | 296 | (2,677) | 163 | (1,592) | 97 | (941) | 57 |

| Archdiocese of S�o Paulo and its suffragan Dioceses | 1,640 | (4,848) | 296 | (2,677) | 163 | (1,592) | 97 | (941) | 57 |

| Archdiocese of Bel�m do Par� and its suffragan Dioceses | 1,640 | (4,848) | 296 | (2,677) | 163 | (1,592) | 97 | (941) | 57 |

| Archdiocese of Manaus and suffragan Dioceses | 1,640 | (4,848) | 296 | (2,677) | 163 | (1,592) | 97 | (941) | 57 |

| Total (shortage) and average repectively | 5,093 | (18,595) | 365 | (10,7247) | 211 | (6,789) | 133 | (4,427) | 87 |

| Figure 18; The evolution of the number of Catholics per priest in Germany and Austria |

| Figure 19; The influence of a true solidarity by Europe and North America on the shortage/surplus of priests as function of the number of Catholics per priest for the entire Church, Europe, North America, Africa and South and Central America |  |

We maintain that this proposal to use viri probati provides a convenient means for a total break with the Church prior to Vatican II, based on and justified by the modernist liberal evolutionary ideology that continuously wishes to detain the Holy Spirit in the ideological Spirit of the Council.

The Cardinals, Bishops and theologians, who make this proposal, especially those from dioceses which still have a luxurious number of priests (figure 18) should be truly ashamed of themselves for abusing the suffering Amazon areas in this way.

Evaluation

This statistical analysis of the Church clerical and lay population has focussed on the shortage of priests, with particular emphasis concerning South and Central America. It shows that:

- The shortage of priests does not concern the Amazon area only. The relative shortage of priests in the sparsely populated areas of the Amazon does not differ significantly from that in the (highly) urbanized locations such as Buenos Aires and Sao Paulo. Therefore, due to the large number of faithful in urbanized areas, the absolute deficit in these areas is a multiple of the deficit in sparsely populated areas.

- The shortage of priests strongly depends on a preferred target for the number of faithful per priest. If this target is set at the actual average of about 3,000 faithful per priest for the entire Church, then the actual shortage for South and Central America is computed to be at least 100,000 priests and is significantly more than the actual number of priests available in South and Central America.

- The religious congregations have potentially lost (primary and secondary losses) at least 265,000 members since the Second Vatican Council. This has handicapped the Church globally, and it therefore affects all humanity. For centuries, these religious worked worldwide at locations with insufficient local vocations, thereby exercising practical Christian solidarity. With the accumulated loss of so many religious, a total lack of Christian solidarity becomes more and more evident, especially at a diocesan level, even between neighbouring dioceses.

- Apart from the fundamental theological objections to the ordination of married men, the consequences for the priesthood would be enormous, if it would indeed be possible to find so many carefully selected viri probati to solve this shortage (table 2). The celibate priesthood would then be completely overwhelmed by these euphemistically called viri probati.

Nothing can remove the culpability of the religious congregations that have contributed to the huge loss of their members since the Second Vatican Council. In particular, those large congregations that are still in severe decline, such as the Jesuits and Franciscans, bear a heavy responsibility in this. The estimated total loss of at least 265,000 religious members since the Second Vatican Council, of which about 50% to 60% are priests, is a number reasonably matching the current shortage of priests in Africa, South and Central America.

This should be one of the main subjects of the Amazon Synod. The Synod should call the religious congregations into account for this. Especially with regard to the general tendency of the sudden decline of religious members that occurred similarly for almost all religious congregations so shortly after the Council. Is that a co-incidence or is it the fruit of a general use of an incorrect and false hermeneutic to interpret the Council documents. A false hermeneutic that is based on the modernist liberal evolutionary ideology and claims to have detained the Holy Spirit by the so-called Spirit of the Council

Therefore, it is most important to research how the reformed religious vows have broken with the original spirituality of their founders and to restore that break. It is especially so, because nowadays still under the flag of the Spirit of the Council this same modernist liberal evolutionary ideology falsely suggests that carefully selected viri probati and the introduction of women deacons is the true solution for the shortage of priests, whereas this shortage actually is the fruit of that same false flag.

References:

a: Emeritus Assistant Professor on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, Delft University of Technology (oostveen@hotmail.com)

Ref. 1: Instruction on certain Aspects of the Theology of Liberation published by the Congregation for Doctrine and Faith on August 6, 1984;

Ref. 2: Address of his holiness Pope Benedict XVI at the Shrine of Aparecida, Sunday, 13 May 2007, on occasion of the fifth general conference of the Bishops of Latin America and the Caribbean;

Ref. 3: Fruits of Vatican II, A Willful Ignorance of an Ongoing Catastrophe, Jack P. Oostveen and David L Sonnier (2016);

Ref. 4:

Ref. 5:

Ref. 6:

Ref. 7:

Ref. 8: